How do you calculate the risks of having a child with Trisomy 21?

June 4, 2014

- Related Topics:

- Genetic conditions,

- Translocation,

- Chromosomes,

- Trisomy/Aneuploidy

A curious adult from the U.S. asks:

"How do you calculate the risks of having a child with Trisomy 21 if the mother is 44 years old, the father is 46 years old and there has already been one miscarriage due to Trisomy 21?"

Editor’s Note (3/24/21): This article has been lightly edited, consistent with the most recent reports from UpToDate.

Two of the three factors you’ve mentioned are important for figuring out the risk for having a child with Trisomy 21 or Down syndrome. Both mom’s age and the previous pregnancy with Trisomy 21 increase the chances, but the age of the dad doesn’t play a big role.

The one that usually matters most is mom’s age. A mom’s chance of having a child with Down syndrome gets higher as she gets older. As you can see in the graph below, a 44-year-old woman has around a 3% chance of having a child with Down syndrome. The flip side of that means she has a 97% chance of not having a child with Down syndrome.

It’s also possible that the previous pregnancy with Down syndrome increases the overall risk. But this is hard to say for sure, and depends on why it happened that first time.

Most cases of Down syndrome happen by random chance, so having one child with Down syndrome usually doesn’t really increase your chance for having a second.

However, there are rare exceptions to this where Down syndrome can “run in a family”. Somewhere between 3-4% of cases are caused by something called a translocation. And while this usually happens randomly, somewhere around 3-4% of the time these are inherited from a parent.

If either parent carries the translocation, then the chances of having another child with Down syndrome go up. If mom has the translocation, the risk is around 10-15%. If dad has the translocation, the risk is only 2-5%. But again, Down syndrome inherited this way is pretty rare.

To get the best information about your specific risk, we would always recommend talking with your doctor or a genetic counselor. They’ll be able to look at your family history, decide if you should test for translocations, and then help you make informed decisions about what to do from there.

Now I want to talk a little bit about why as a woman gets older her chances for a child with Down syndrome increase. Then we will talk about the type of Down syndrome that can “run in a family.”

The Problem with Older Eggs

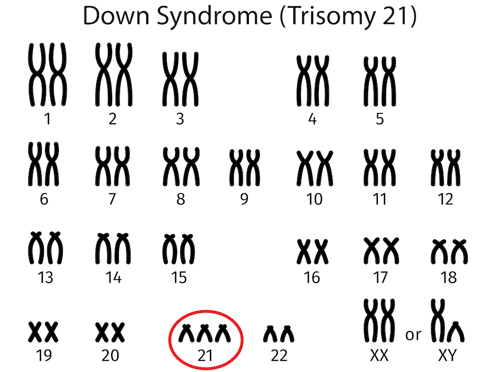

We can’t talk about Down syndrome without talking about chromosomes. You might remember that chromosomes are the packages of instructions that are in every cell of our body. They tell our bodies what to look like, how tall to grow, and how to function.

Humans usually have 23 pairs of chromosomes. We get one of each pair passed down from mom and one of each pair from dad.

Sometimes, there is a random mistake when the sperm or egg is being made. This causes there to be extra or missing chromosomes passed down from that parent (“aneuploidies”). If this happens with an extra copy of chromosome 21, it causes Down syndrome.

This happens by random chance, but this chance goes up as a woman gets older. This is because women are born with all of the eggs they are ever going to have and as a woman gets older, her eggs get older too.

So the older the egg is when it is getting ready to package only half of the chromosomes to pass down (one of each pair), the higher chance that a chromosome pair will get stuck together. This is what happens with Down syndrome, the chromosome 21 pair gets stuck together.

A mistake in packaging of chromosomes can happen with dad too, but the chances really don’t get higher as dad gets older. That is because men are constantly producing new sperm every couple of weeks, so there isn’t a higher chance that the chromosomes will get stuck together.

These random mistakes cause almost all cases of Down syndrome (and other trisomies). For that reason, you usually just estimate the overall risk of Down syndrome based on the age of the mother.

Balanced Translocations

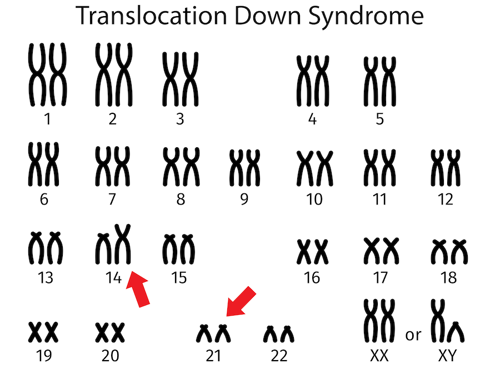

Now let’s talk about the rare type of Down syndrome that can “run in families.” About 3-4% of cases of Down syndrome are caused by something called a Robertsonian translocation, also known as Translocation Down syndrome.

In this type of Down syndrome, the extra copy of chromosome 21 is attached to a different chromosome. This can happen randomly or be inherited from a parent.

Here’s an example of what that looks like, where the extra copy of chromosome 21 is attached to the top of chromosome 14:

Even though it is arranged differently, there are still three copies of chromosome 21 and this still causes Down syndrome.

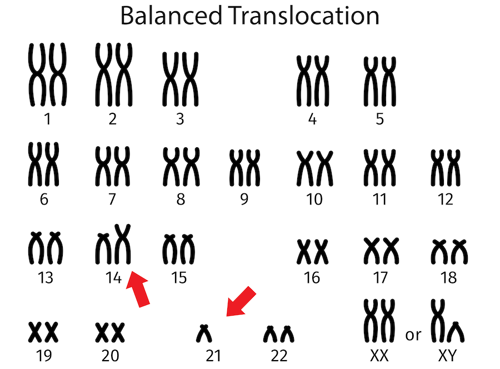

To see if it was inherited, you have to see if one of the parents has a translocation as well. This can be done by a blood test on each parent.

If Down syndrome was inherited, one parent would have chromosomes that looked something like the picture below:

Here one copy of chromosome 21 is attached to chromosome 14, but there is only one other copy of chromosome 21. This is called a balanced translocation. The parent has the typical number of chromosomes just arranged in a different way so the translocation usually does not cause any health problems for the person.

The reason it can be helpful to know if Down syndrome was caused by a translocation is because it will change your risk. If a parent has a balanced translocation, the chance of passing down an extra chromosome to a child depends on which parent has the translocation. There is about a 2-5% chance for Down syndrome to happen again if dad has the translocation and about a 10-15% chance if mom has the translocation.

Conclusion

Down syndrome usually happens randomly, though in rare cases it is inherited from a parent. For that reason, a previous pregnancy with Down syndrome doesn’t increase your overall risk by very much. The mother’s age is what has the biggest impact on risk.

Author: Katie Kobara

When this answer was published in 2014, Katie was a student in the Stanford MS Program in Human Genetics and Genetic Counseling. Katie wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation