Are chimeras at an increased risk for any diseases?

March 10, 2020

- Related Topics:

- Chimera,

- Neurodiversity,

- Microchimerism,

- Medical genetics,

- Autism

A curious adult asks:

“Are chimeras at an increased risk for any diseases? I've heard there is a link to autism.”

Before we dive in, it’s important to remember the distinction between association and causation. There have been associations between chimeric status and specific conditions. Autism is not among these conditions.

However, it has not been proven that chimerism causes these conditions.

There are several different types of chimeras, some of which have been seen to be associated with disease. (Read more about different types of chimerisms here.)

Twin chimerism

Twin chimerism arises from cases of “vanishing twin”. This can happen within a twin pregnancy, if one embryo dies in utero and is absorbed by the surviving embryo. The surviving fetus then has two sets of DNA: its own DNA, and DNA from its twin.

It’s hard to study this phenomenon in natural pregnancies. But it is possible to study this in pregnancies that occur as a result of fertility treatments. In those cases, you know exactly how many embryos were transferred to the womb, and you know exactly how many babies were born.

One study showed that the “vanishing twin” phenomenon is associated with an increased risk of congenital birth defects in the surviving fetus.1 This suggests that a lost twin may be a factor for the health of the surviving twin.

Studies of disease in twin chimerism are continuously ongoing. Confirmed cases of twin chimerism are very rare, with only 100 identified worldwide. So right now, not much is known about the health effects (if any) in this type of chimera.

At this point, disease has mostly been implicated in another type of chimerism: microchimerism.

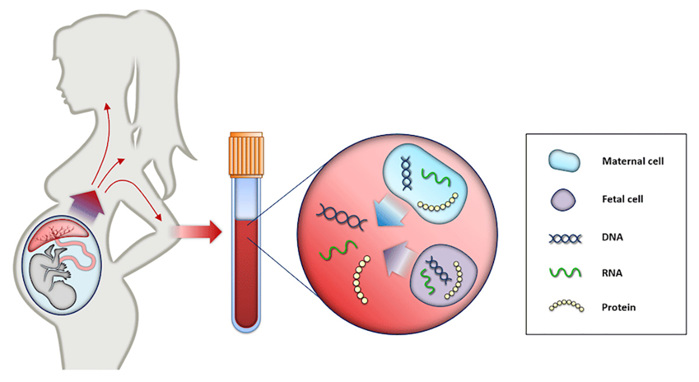

Microchimerism from pregnancy

Mothers are a tiny bit chimeric! Occasionally, a few cells from a fetus may stick around even after the baby is born. This means that mothers may have a secondary set of DNA in their bodies!

It’s a very small amount though. Hence microchimerism.

Microchimerism and disease

When this secondary DNA is introduced, the body sometimes recognizes it as a foreign substance and attempts to get rid of it.3

Theoretically, this could trigger the mother’s immune system so much that she develops an autoimmune disease. Autoimmune diseases are conditions in which your immune system mistakenly attacks your own body.

One study looked at women who had sons versus women who did not have sons. This is one of the easier types of microchimerism to detect, since normally women do not have male cells!

They found that mothers with microchimerism were more likely than non-mothers to have system sclerosis, a chronic condition that involves hardening and tightening of the skin.4

But microchimerism does not always increase risk for disease. Sometimes it’s even beneficial!

In fact, it’s well known that multiple pregnancies actually provides a protective factor against breast cancer.5 This may be due to multiple opportunities for microchimerism to occur, but the exact reason for this is not yet known.

This theory is supported by some other research. One study found that there were higher concentrations of fetal DNA near thyroid tumors than expected.6 This suggests that fetal cells may be recruited by the body to assist in repairing tumor sites.

But what about autism?

No associations between autism and microchimerism have been reported. Autism is a very confusing condition as not that much is known about it. What we do know is that both genetics and environment play a role.

Clearly, microchimerism affects different organ systems, so who is to say that the brain is off limits? More studies would need to be done in this area to see if neurological conditions (like autism) are related to chimerism.

The landscape of chimerism is just beginning to unfold. Many associations have been made between chimeric status and conditions such as autoimmune diseases and cancer. This alone can help scientists to continue to make breakthroughs in medicine and provide insight into future treatments!

Author: Kathryn Reyes

When this answer was published in 2020, Kathryn was a student in the Stanford MS Program in Human Genetics and Genetic Counseling. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation