How does RNA polymerase recognize the transcription start site?

August 8, 2019

- Related Topics:

- Noncoding DNA,

- Transcription and translation,

- Gene expression,

- Molecular biology

An undergraduate student from Egypt asks:

"After the RNA polymerase and the transcriptional initiation complex bind to the promoter, how can it recognize the transcription start site? How does it know which base is the first base to start the transcription process? And for saving time I will add another question: How can the same promoter guide bi-directional transcription in opposite strands?"

This is a great question! A lot of things work together to set the start site of a gene. And different combinations of these things can get the job done, so there's no single rule for what a transcription start site looks like.

That said, two major players are: the DNA sequence itself, and a protein called TFIIB.

But before we dive into the details, let's make sure we're all on the same page. What is "transcription" and why does it matter?

What does it mean to read a gene?

All of our genetic information is stored in our DNA, which sits inside the nucleus of our cells. But, we need to get this information to other parts of our cells, too.

This is where a process called transcription comes in, where our DNA is copied into RNA. Transcription is really useful because the RNA copy can travel anywhere that's needed in the cell, while the DNA stays safe in the nucleus.

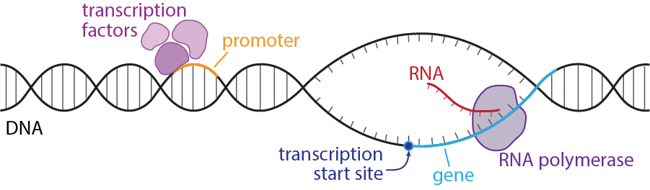

So what's actually doing the copying? It's a protein called RNA polymerase, which is like a little machine that slides along our DNA and spits out the RNA version of what it's reading.

Now, we don't want RNA polymerase running wild all over our DNA and making tons of RNA. If that happened, our cells would be getting all kinds of instructions at the wrong times, and things would get out of control!

Our cells don't want that. So, they have other protein machines that control where and when transcription happens. We've cleverly named these controller proteins transcription factors.

Transcription factors cut and unwind DNA's twisted double helix shape so that it's ready to be read over. They also call RNA polymerase over, so it knows that this part of the DNA needs to be copied.

Transcription factors only hang out at certain DNA sequences. These sequences, called promoters, happen just before the start of our genes.

Promoters make sure that RNA polymerase only gets called to genes, and not to other parts of our DNA. But, there's still a bunch of DNA bases between the promoter and the spot where RNA polymerase actually begins reading: the gene's transcription start site.

So now we're ready to tackle the question, "How does RNA polymerase know where to actually start reading our DNA?"

The transcription start site fits into place

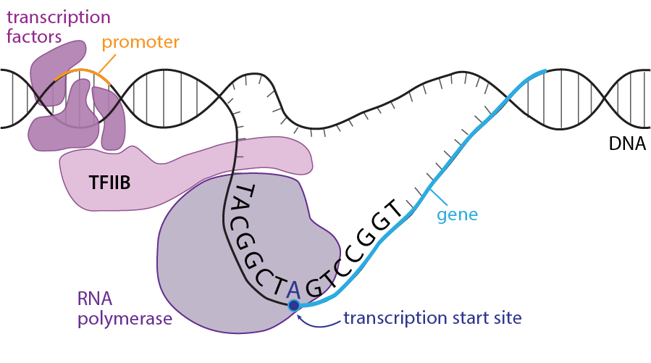

Each transcription factor has its own part to play in starting transcription. The one that's most important for figuring out exactly where transcription will start is called transcription factor II B, or TFIIB.

TFIIB's job is to grab onto RNA polymerase, and connect it to the DNA and the rest of the transcription factors.

All of these proteins fit around the DNA in a very specific way, like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. TFIIB's shape pushes RNA polymerase just a bit further along the DNA than all of the transcription factors.

This short distance - around 30 bases of DNA - sets up the RNA polymerase almost exactly at the transcription start site! [1, 2, 3]

So, the shapes of transcription factors do some of the work in finding the transcription start site. The next step depends on the DNA sequence itself.

A certain DNA pattern helps mark the transcription start site

Thanks to TFIIB, the RNA polymerase is almost where it needs to be to start reading the gene. So it begins scanning the DNA, looking for the exact right spot to begin.

To find this spot, the RNA polymerase is searching for a certain combination of DNA bases (a "motif") that marks the beginning of genes. Different genes can use different starting motifs.

Scientists have been trying to figure out the bare minimum of DNA bases needed for a gene to start. The simplest motif they've come up with so far is "YR", where the RNA polymerase starts reading at the "R".

But usually we talk about DNA using the letters A, C, G, and T! What does "YR" mean?

Well, it means that there are options for each spot. The "Y" means that the DNA base can be a C or a T. And the "R" can be an A or a G.

So, our transcription start sites don't always have to be the same letters. This is really important, because it means our DNA can have more variety.

This lets us develop our own unique DNA codes, while still making sure all of those important DNA instructions get read

Our DNA can be read in two directions at once

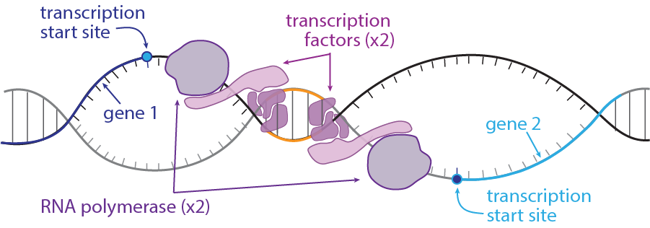

DNA has a double helix shape, where two strands of DNA are lined up with each other and twisted into a spiral. There are genes on both strands of our DNA that need to be read.

When genes are right beside each other but on different strands of DNA, they're often expressed at the same time.[4] This is called bidirectional transcription.

Scientists originally thought that these gene neighbors share transcription factors, and that RNA polymerase has to figure out which direction to read the DNA.

But what actually happens is that each neighbor calls its own set of transcription factors to the DNA. And remember how the transcription factors fit around the DNA like a jigsaw puzzle?

The transcription factor puzzles for these neighbor genes are flipped around versions of each other. And the direction they point tells the RNA polymerase which direction to start reading in.[5]

So if gene neighbors don’t use the same transcription factors, why are they usually expressed at the same time? Scientists aren’t 100% sure, but here are two pretty good guesses:

- When transcription factors hang out at one promoter, they might call over even more transcription factors. These extra transcription factors could end up at neighboring promoters.

- Part of the job of transcription factors is to unwind and open up the DNA so it’s easier to read. This change in the DNA’s shape could spread out and affect nearby genes, too.

Author: Olivia de Goede

When this answer was published in 2019, Olivia was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying long non-coding RNAs in the immune system in both Karla Kirkegaard's and Stephen Montgomery's laboratories. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation