What is the Bombay blood group?

July 13, 2018

- Related Topics:

- Common questions,

- Blood type,

- Bombay blood group,

- Rare events,

- ABO blood type,

- Molecular biology,

- Genes to proteins

A curious adult from the US asks:

“What is the Bombay blood group?”

Bombay blood group is a rare blood type. People with this blood type always show up as type O on a blood test. But they can have hidden DNA for other blood types, which they may pass on to a child.

This very rare blood type is most “common” in southeast Asia. For example, around 1 person in 10,000 has this blood type in India. It’s much rarer in other parts of the world. It’s literally a 1-in-a-million event in people with European ancestry!

It’s so rare that people with this blood type can’t reliably get a blood transfusion, and may have to find donors internationally.

An Order of Operations

Perhaps you have heard of the “blood type gene”. The ABO gene can come in three different versions: A, B or O. The versions you inherit determine whether your blood is type A, type B, type AB, or type O.

When we talk about the genetics of blood type, we typically only refer to the ABO gene. And that’s okay. Usually we don’t need to go into greater detail. (Read more about ABO blood type here.)

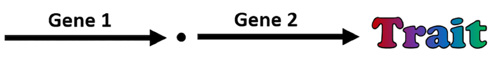

But Bombay blood group is caused by a different blood type gene, FUT1. These two genes both affect blood type, and act in sequence with each other.

When one gene requires another to act before it, it is called epistasis. We say that the first gene to act in a sequence is epistatic to the second gene. In this relationship, the first gene to act controls the trait.

One example of epistasis is baldness. Baldness is epistatic to hair color. If you get the gene for baldness, it does not matter what gene you get for hair color. You will be bald.

This is where Bombay blood group comes in. People in the Bombay blood group have a broken version of a gene that is epistatic to ABO. That gene is FUT1.

If you have two broken copies of the FUT1 gene, it doesn’t matter what ABO versions you have. You will have type O blood.

It’s worth noting that the Bombay blood group is quite rare. It was only first discovered in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1952. It affects one person out of 10,000 in India. It is a bit more common in Taiwan, where it affects one person in 8,000.

It’s even rarer in other parts of the world! Among people of European ancestry, Bombay blood group is literally a one in a million event.

But as rare as it might be, it does happen. And when it happens, it can result in unexpected patterns of inheritance.

A Protein Team

Let’s look at what happens with Bombay blood group at the molecular level.

In genetics, we like to talk about which versions of a gene produce which traits. But when we do this, we are skipping a few steps. Genes don’t produce traits directly. Instead, each gene helps make a specific protein. Then, those proteins do things in the cells of our body. The overall effect of those proteins is what we call our trait.

Our blood type trait is the result of several genes working together, including ABO and FUT1. The proteins made by these genes decorate your red blood cells with chains of sugars.

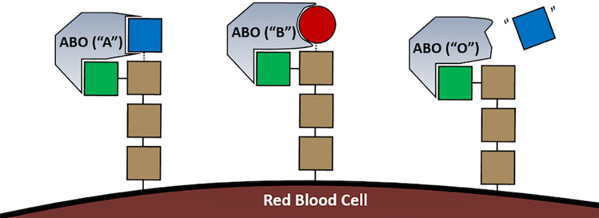

The protein made by the ABO blood type gene attaches the last sugar to this chain. If you get the A version of the ABO gene, the protein attaches one kind of sugar. If you get the B version of the gene, it attaches a different sugar. The O version of the ABO gene doesn’t attach any sugar at all!

So now you know what blood type really means! It is based on the identity of the last sugar in a chain that hangs off of your red blood cells.

This is where Bombay blood group comes in.

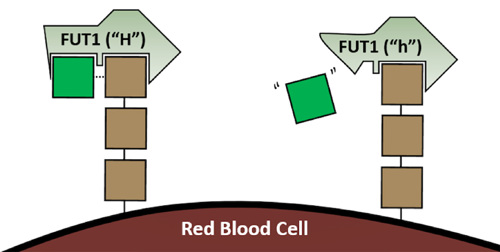

The FUT1 gene makes the second-to-last protein to act on the sugar chain. FUT1 comes in two versions: a working H version and a broken h version. The protein made by the H version properly puts a sugar on the chain. The protein made by the h version does not attach the sugar to the chain.

The versions of FUT1 are called H and h for a reason. When the H version of FUT1 attaches a sugar to the chain, the chain is called the “H antigen”. When the broken h version of FUT1 fails to attach a sugar to the chain, the H antigen is not formed.

The H version of FUT1 is dominant to the h version. If you get one working H version of FUT1, it is enough to do all the work. The blood cells all get the H antigen.

So what does this have to do with blood type?

The protein from the ABO gene adds its sugar on to the H antigen. The A version of ABO changes the “H antigen” to the “A antigen”. The B version of ABO changes the “H antigen” to the “B antigen”. The O version doesn’t change anything. People with type O blood have the H antigen hanging from their red blood cells!

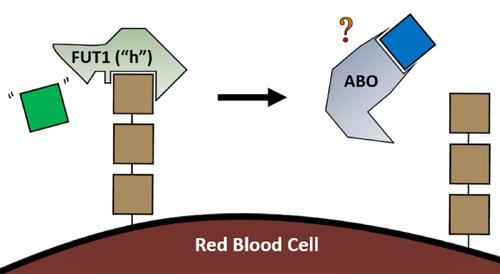

People in the Bombay blood group have two broken h versions of FUT1. As a result, they can’t make the H antigen.

The protein made by ABO will only attach its sugar to the H antigen. So if you are in the Bombay blood group, and you don’t have any H antigen, your versions of ABO do not matter. Without the H antigen around, none of them will be able to do their job.

So why do people in the Bombay blood group test as type O? I mentioned that type O blood features the H antigen. But people in the Bombay blood group don’t make the H antigen. What’s the deal?

The answer has to do with how we test for blood type. People in the Bombay blood group don’t have the H antigen. They also don’t have the A antigen or B antigen.

Blood tests don’t look for the H antigen. They are only looking for A and B. Someone who doesn’t have A or B is assumed to be normal type O. So, the blood test simply can’t tell the difference between type O blood and the Bombay blood group.

Read More:

- An O parent with Bombay blood can have an AB child

- Other unusual blood types can also lead to children with unexpected blood types, including Cis-AB, Chimerism, and Rare mutations

- People in the Bombay blood group must receive blood from other people in the Bombay blood group. They often have to find donors internationally.

Author: Robert Coukos

When this answer was published in 2018, Robert was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying protein engineering and directed evolution in Alice Ting's laboratory. He wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation