When scientists clone an animal, how do they reprogram the DNA?

January 29, 2018

- Related Topics:

- Genes to proteins,

- Developmental biology,

- Molecular biology,

- Gene expression,

- Genetic engineering,

- Cloning

A high school student from Tennessee asks:

“When scientists clone an animal, how do they reprogram the DNA to make an embryo instead of whatever the cell used to be? I know it’s called “somatic cell nuclear transfer,” but how does moving the nucleus into an egg reset its DNA?”

The really short answer is that scientists don’t change the DNA itself. The egg has the stuff it needs to read the parts of the DNA instructions necessary to make an embryo.

The egg can “open up” or “unroll” the parts of the DNA needed to get the egg to start on the journey towards developing into a baby. To do this, it uses something in the egg called “pioneer factors.”

Different Cells Use Different Parts of the Same DNA

DNA has all the instructions for making a living thing. Each individual instruction is called a gene. But it’s not like the cell uses all the instructions at once.

You can think of the DNA in a cell as kind of like a bunch of scrolls full of magic spells. You don’t need every single spell to bring a thing to life.

Yeah, some spells will be useful (let it use energy!), but some spells won’t (make the color brown!). And some might even be downright dangerous (kill it!).

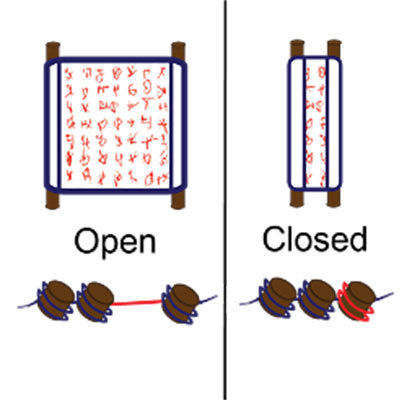

So really reprogramming is unrolling the scrolls you need and rolling up the ones you don’t. Or, to put it another way, turning on the right genes and turning off the wrong ones.

DNA is Rolled Up in Proteins

Obviously, our genes aren’t paper wrapped around a stick. However, the truth isn’t too far off. The DNA that makes up a gene is wrapped around individual proteins called histones.

Remember the individual instructions in the DNA called genes? Well, they don’t do anything as DNA.

Instead the instructions are read by the cell and ultimately turned into proteins. It is these proteins that do the work in a cell.

Histones are one of these proteins. They are the “spool” around which DNA is wound.

If the gene is tightly wound, it’s hard for the cell to open it up and read it. In a skin cell, the genes involved in making an embryo develop into a baby are tightly wound. The cell can’t read them.

Going back to the spells, histone genes are like a spell that makes the sticks the scroll wraps around. You can then come up with other spells to change the sticks, too.

You can have a spell that will keep a scroll tightly wrapped up (which might be useful for the “kill it!” spell) and another that will let you unwrap the scroll easily (probably better for the “let it use energy” spell).

In your cells, there are actually proteins that cause the other histones to stick close together (so the gene can’t be read), and others that space the histones out or knock them off so it’s easy to read the genes.

Pioneer Factors can Open Closed DNA

Biologists use the word “factor” in a way that others might use the word “thing”. So a “transcription factor” is a thing (in this case different kinds of proteins) that helps with transcription.

Transcription is when the DNA is copied into RNA. DNA and RNA are chemically pretty similar in the same way that your spoken words are similar to the written words Siri writes or “transcribes” for your text messages. Before a gene can be translated into a protein, it has to be transcribed into RNA.

There are a lot of different transcription factors and they all help read DNA. Some of these transcription factors directly recognize specific parts of the DNA. Most transcription factors can only read DNA if it’s already slightly open.

However, some transcription factors, the “pioneer factors” can actually open up the DNA. Yes, scientists really call them pioneer factors.

Like the pioneers of the old west, they find where they need to go all on their own, settle down, and other factors come to them. Pioneer factors push the histones out of the way so the other proteins can read the DNA.

Eggs are Full of Pioneer Factors

Before eggs are fertilized, their DNA isn’t being read. Mom gave the egg all the proteins it would need to start going from one cell to a full organism.

Sperm DNA is really, really tightly wound around proteins. This is good for the sperm because it lets it pack a lot of information in a little space and zoom it off towards the egg. Once the egg and the sperm meet, the egg needs to unpack and turn on both sets of DNA.

That’s where the pioneer factors come in. They can find the spells for early cell development among all the closed scrolls. And they’re good at it.

They’re so good at it, they can even do it in the DNA from a cell that isn’t from an egg—a somatic cell nucleus. “Somatic” just means not an egg or sperm, and the nucleus is where DNA is stored in a cell.

In fact, this is where the type of cloning you are talking about gets its scientific name—somatic cell nucleus transfer. The nucleus from a cell like a skin cell is transferred into an egg.

By finding the right spots and moving the histones around in the DNA, the pioneer factors start the process of early development.

The pioneer factors do need a little convincing, though. After scientists swap out the DNA, they shock the cell with electricity or put chemicals on it to trick it into thinking it was just fertilized. This causes the pioneer factors mom left to get to work!

Pioneer factors are kind of like throwing a “find all the useful spells” spell at your big pile of scrolls. The somatic cell had its own spells open (for making a skin cell or wherever it came from) and had wrapped up the “early development” spells.

The egg’s pioneer and other factors can override the old instructions, reprogramming the somatic cell. Since the cell no longer has the old “be skin” transcription factors, it forgets how to be skin and starts turning into a whole new living thing.

Author: Nikki Teran

When this answer was published in 2018, Nikki was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying repetitive DNA at the centromere in Aaron Straight's laboratory. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation