How do paternity tests work?

November 29, 2018

- Related Topics:

- Paternity tests,

- Consumer genetic testing,

- Genetic variation,

- Genetic testing

A curious adult from the UK asks:

“How exactly do paternity tests work? I have recently had a paternity test carried to determine if a man is my father. They tested 24 markers and we matched on 14 of them. The testing company said that he can’t be my father. My question is how can two people have 14 matching markers and not be related?”

Paternity tests can be hard to understand. Matching with someone at 14 out of 24 markers seems like a lot, but these tests are designed so that a parent and child should completely match. And even though they're usually described as "paternity" tests, the same type of test can be used to confirm either parent.

To figure out why all of the markers should match between a parent and child, let’s break down how paternity tests work.

Paternity tests look at variable parts of our DNA

Maybe you’ve heard that people get half of their DNA from their mom, and half from their dad. But, even unrelated people are genetically very similar -- over 99% of DNA is shared in humans! This makes it tricky to figure out which bits of DNA are shared with someone else because we’re actually related, and not just because everyone has that same bit of DNA.

Luckily, there are some parts of DNA that vary a lot between people. These are what paternity tests look at.

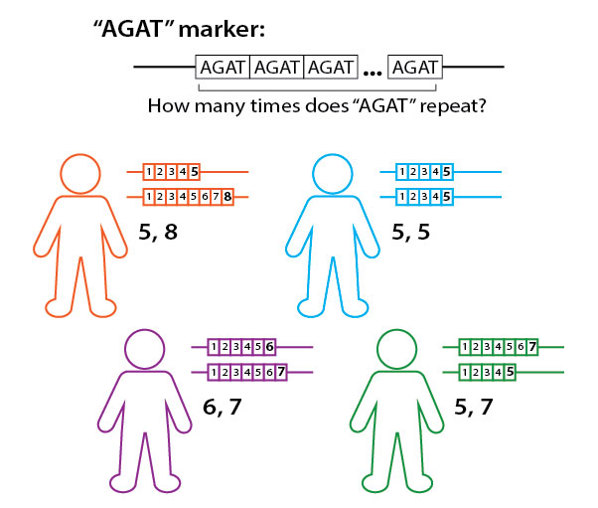

At these places, some of the letters that make up our DNA (A, C, T, and G) are repeated a bunch of times. For example, some people could have the letters “AGAT” 7 times in a row, others could have it 6 times, and others could have it 8 times.

For a 24-marker paternity test, if the person being tested was the biological parent, we’d expect that all 24 markers should match up.

Now, you might be wondering how these super-different parts of DNA affect us physically. The answer is that they don’t!

Most of these repeating letters are in stretches of DNA that don’t get read by our cells. So, it doesn’t matter how many times these bits of DNA repeat. This is what lets them vary a lot between people.

Since we all have two copies of DNA (one from each parent), we each have two copies of each of these markers. Different people have different pairs of these repeats.

So, what does a “match” look like?

Let’s say that we’re looking at a marker where a child has a bit of DNA repeating 9 times on one copy of his DNA, and 11 times on the other. We then measure his mom and dad at that same marker. Mom has 9 and 13 repeats, and Dad has 8 and 11 repeats.

Since the child got half his DNA from his mom and half from his dad, his two copies of the marker should be able to be tracked back to either his mom or his dad. This checks out: his 9 repeat came from his mom, and his 11 repeat came from his dad. So, it’s a match!

That said, it’s possible for markers to match up just by chance.

If you think about the example above, there are probably lots of people that have an 11 repeat as one of their copies of that marker. This means that we need to test a bunch of markers to be sure of paternity.

For a 24-marker paternity test like the one you took, if the person being tested was the parent, we’d expect that each marker would play out like the example above. That means that all 24 markers should match up.

In your case, 10 of the markers didn’t work out with the person being tested, which is a lot of mismatches. We can be confident that he is not your father.

There can be exceptions to 100% matching between a parent and their child. Sometimes, mutations in DNA can cause a mismatch. This is described in detail here. However, that would only cause 1 or 2 mismatches, not the 10 mismatches that you’ve seen in your paternity test.

The chances of totally matching with someone you aren’t related to are really small

So, what’s the chance of a child totally matching with someone who’s not their parent? Well, a couple of papers crunched the numbers for 12-15 marker paternity tests.

Over 99.96% of all unrelated people have 2 or more mismatches. To flip that around, fewer than 1 in 2,000 unrelated people will have 11/12 or 12/12 matches.

And for a perfect, 12/12 match? The chance of two unrelated people completely matching is less than 1 in 50,000!

When you bump it up to 24 markers, the odds of two unrelated people matching up are even smaller.

Ancestry tests are a more sensitive option

As we figured out earlier, the more markers we test, the surer we can be in the results. So, instead of just testing 12 or 24 markers with a paternity test, another option is to use ancestry tests. These compare hundreds of thousands of spots in the DNA!

These tests are provided by companies like 23andMe or AncestryDNA, and their main goal is to help us understand our ancestry. But they can also be used to test relatedness: all of those extra markers make them a more sensitive option, and they can even be cheaper than paternity tests!

Having said that, ancestry tests are not currently admissible in a court of law. So depending on your needs, a traditional paternity test may still be the best option.

If you want to learn more about how ancestry testing can be used to figure out relatedness, check out this link.

Author: Olivia de Goede

When this answer was published in 2018, Olivia was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying long non-coding RNAs in the immune system in both Karla Kirkegaard’s and Stephen Montgomery’s laboratories. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation