Can you tell whether a person’s parents are related from their DNA?

January 4, 2017

- Related Topics:

- Relatedness,

- Intermarriage,

- Consumer genetic testing,

- Complicated family trees,

- Genetic genealogy

A curious adult from Michigan asks:

"Is there any way to tell if someone is the product of incest like father/daughter by just looking at their DNA? Not testing the parents?"

That's an interesting question! It may actually be possible to get some idea about how related your parents are, but you probably won't be able to say conclusively. The only way to know for sure would be to test the parents or another relative.

One way you can use your DNA to see if your parents might have been related is through a program like GEDmatch's "Are your parents related?" app.

It can look for telltale signs in your raw data from a company like 23andMe that your parents are related. And it can give some idea about how related they might be.

I'll explain how a program like GEDmatch might be able to tell if a person's parents are related from just looking at that person's DNA. Then I'll talk about why having the DNA from the parents would let you know for sure.

DNA Mixes Between Generations

To understand how we can test someone's DNA to check if their parents were closely related, we need to know a little more about how DNA works.

DNA has the instructions for making us. Since we all look a little bit different, it's not surprising that our DNA is different, too.

Some people are tall and others are short, some have blue eyes and some have green or brown. These differences are coded in our DNA.

Our DNA is stored in our cells as 23 pairs of chromosomes. You've probably heard that you get half of your DNA from mom and half from dad. That's because we get one chromosome of each pair from mom and one from dad.

Let's look at a person whose parents aren't related. If the parents are unrelated, then the chromosomes in each pair are very different from one another.

For example, one pair of dad's chromosomes might look like this:

Dad has two different-looking chromosomes because the DNA is slightly different in each. That's because he got one of the pair from his mom and a slightly different one from his dad. (Remember he has 22 other pairs as well.)

Now let's add mom (in red). She also has two different chromosomes.

Now let's have them have a child.

In a simple world, you might think that each parent would pass one or the other of the chromosomes in a pair. But as you can see in this image, life is not so simple!

As you can see, the child does have one copy from their mom, and one from their dad. But before they got handed down to the child, there was a mixing step that happened. This mixing is called recombination.

When this happens, pieces of the chromosome are swapped between pairs. That's why mom starts out with two different-looking chromosomes and her child ends up with a chromosome that looks like a mix of the two. This swapping happens with dad's chromosomes, too.

When this child has children of their own, the same swapping will happen between their chromosomes.

Imagine that this child has a child with an unrelated partner (in purple). The second-generation child ends up with one chromosome that's a mix of the original mom and dad (red and blue). The other chromosome is a mix of their other parent's chromosome (purple). And this mixing carries on through the generations.

Related Parents Have More in Common

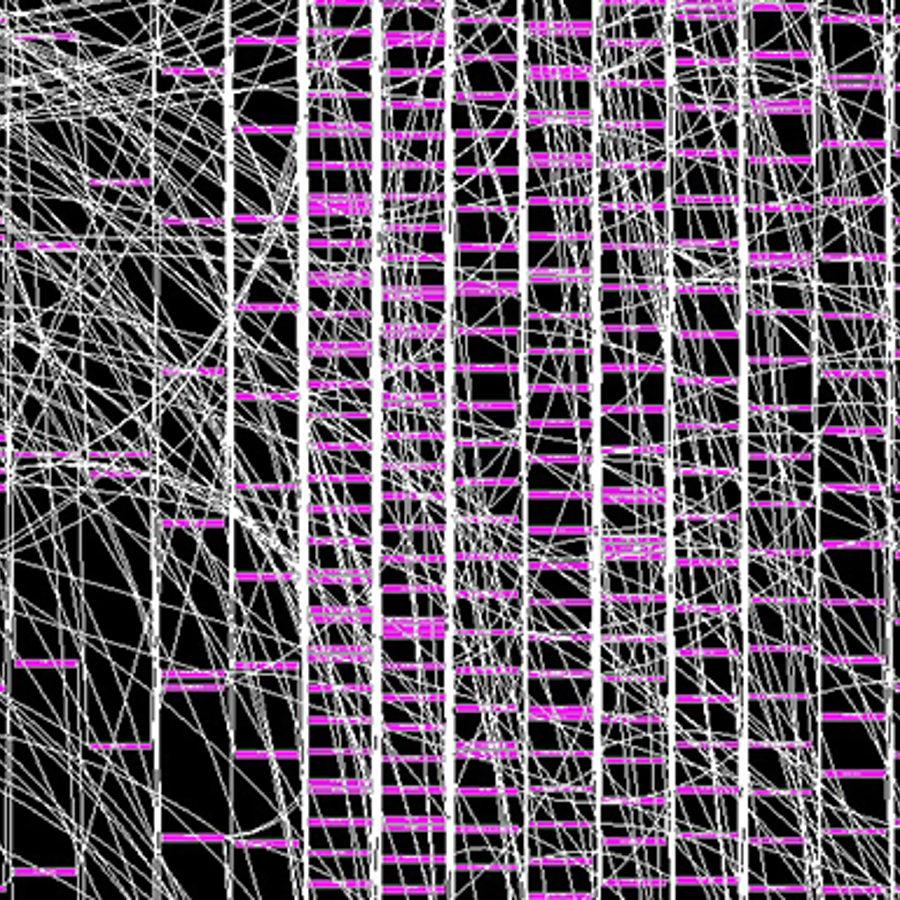

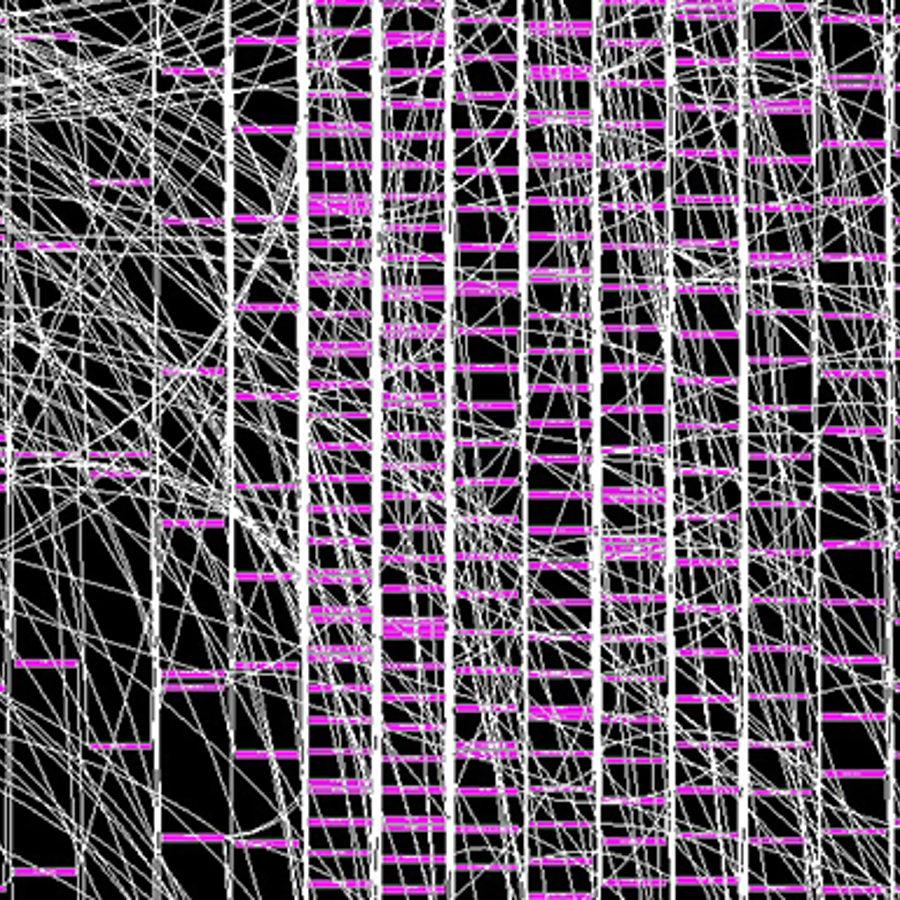

Now that you understand how recombination works, let's see what the DNA would look like if the parents are closely related.

Let's look at our original set of parents again. Imagine they have two children. Those children both get a mix of dad's chromosomes and a mix of mom's chromosomes in their pair.

As you can see, they don't get the same exact mix of DNA from each parent. That's because the swapping is different every time recombination occurs.

They do have some pieces in common though. Now let's see what would happen if these two siblings had a child of their own.

First off, you can see that the swapping happened again. But you can also see a few parts of each chromosome in the pair that look the same.

To make this more clear, below is the child with unrelated parents next to the child with related parents. DNA that is identical is shown with a gray box.

The areas that are the same are "runs of homozygosity," which means parts that are the same on both chromosomes.

As you can see, only the child with related parents has any significant amount of this DNA. The child with the unrelated parents has none of these runs of homozygosity. This is because the chromosomes of the child with closely related parents are very similar to begin with.

Scientists can check for these regions in a person's DNA, and count how many there are. Children born to unrelated parents will have relatively few of these areas.

However, if there are many runs of homozygosity, this might be a sign that the child was born from closely related parents. And you don't need the parents' DNA to look at this. You only need to look at the child's chromosomes.

In fact, a 2011 study did just that. They reported that they were able to identify several children with large areas of the same DNA in their chromosomes (about 25% of the total DNA).

Still, the only way to be certain is to look at one or both parents, too.

Look at Mom and Dad's DNA

To confirm that someone's parents are closely related, you'd have to test the DNA of the parents. We could use conventional DNA tests to compare the DNA of the child and their family members.

We know that on average, a child shares 50% of their DNA with each parent, and siblings have 50% of their DNA in common. So if a child is born from incest between siblings, that child would likely share more than 50% of their DNA with each parent.

In the case of incest between a parent and a child, the child would share more than 50% of their DNA with their parent/grandparent, instead of the 25% expected between grandparent and grandchild.

Author: Fiona Tamburini

When this answer was published in 2017, Fiona was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying genetic interactions between humans and microbes in Ami Bhatt’s laboratory. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation