Can Sertoli Cell Only Syndrome be inherited?

November 7, 2013

- Related Topics:

- Medical genetics,

- Y chromosome,

- Mutation

A graduate student from the U.S. asks:

"My friend's husband has Sertoli Cell Only Syndrome. Will they be able to have children, and if so, what are the chances that a son would also get Sertoli Cell Only Syndrome?"

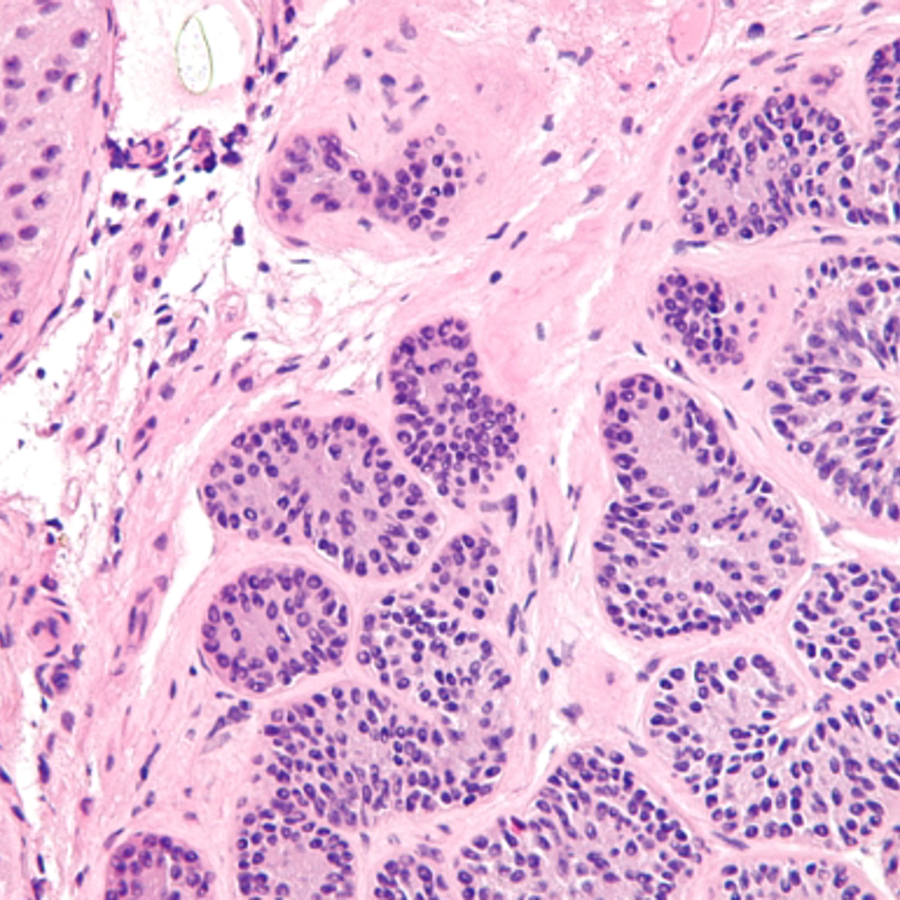

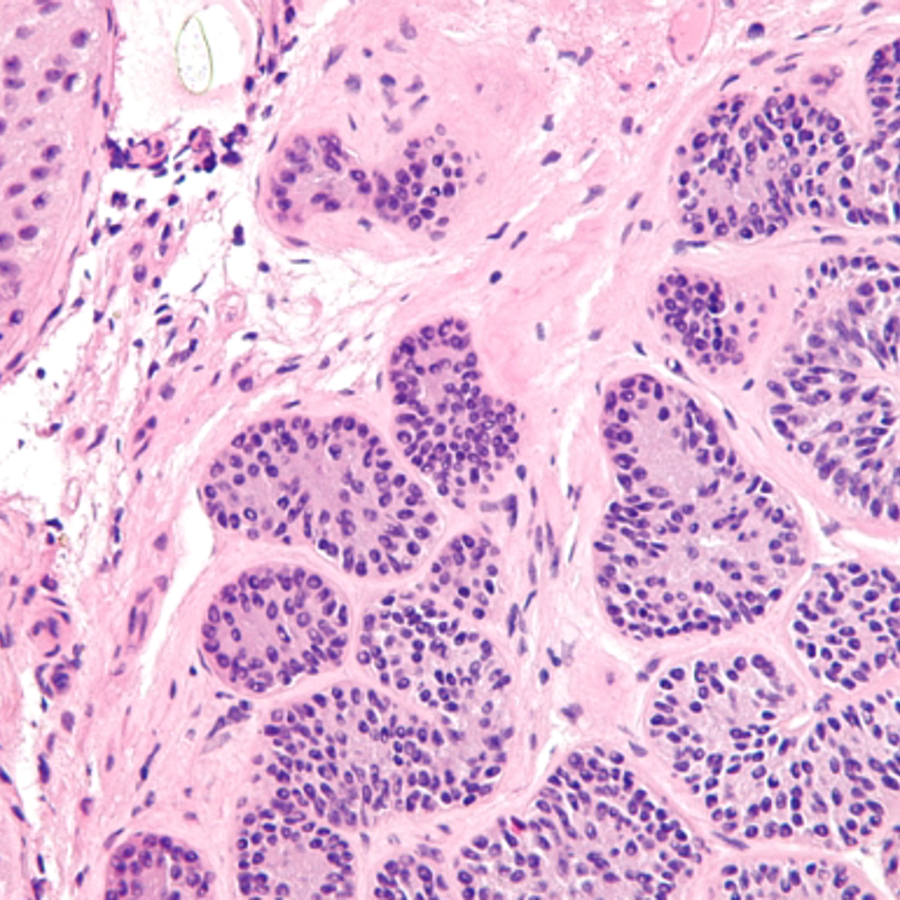

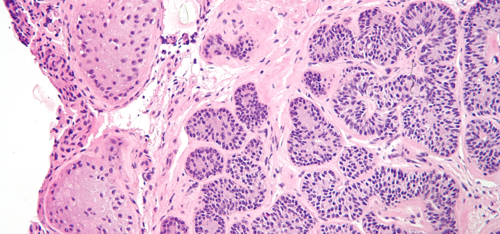

Most men with Sertoli Cell Only Syndrome (SCOS) can’t make sperm. This means, of course, that most of these men can’t have biological children. But there are exceptions.

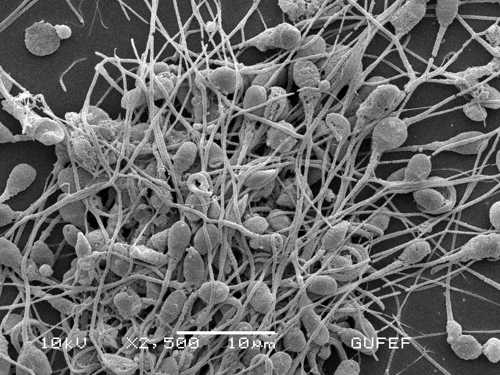

Every now and then a man with SCOS can manage to make a few sperm. These men don’t make enough to have kids the old-fashioned way, but there are ways they could still have kids. For example, their sperm could be directly injected into an egg.

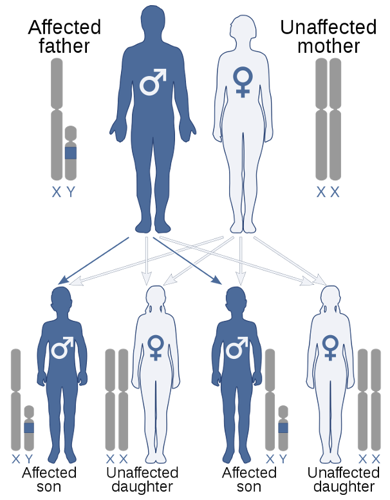

If your friend’s husband is one of the few men that can make at least a few sperm and if the injection works, then odds are that any sons he conceives would have the disease too. But none of his daughters would. And importantly, his daughters would not pass it on to their sons. The SCOS would end with him.

There are a few situations where a man with SCOS might have a son that doesn’t end up with the same disease. In these cases, the dads did not end up with SCOS for a genetic reason. They have SCOS because of trauma, chemical exposure, radiation or some other environmental reason.

Still, many cases are genetic which means his sons would probably end up with his SCOS (assuming he can make any sperm whatsoever). For the rest of the answer, I want to focus on why only his sons would be at risk and why his daughters won’t pass it on.

Then I want to go into where his genetic SCOS might have come from in the first place. After all, if men with SCOS can’t father children, how did your friend’s husband get it?

Y It Ends With Him

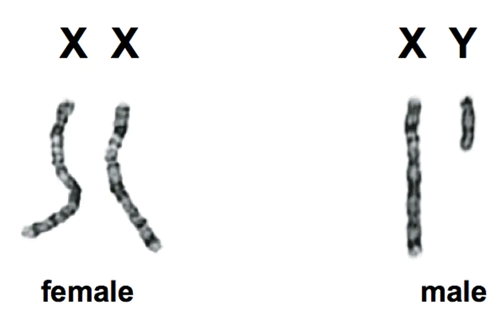

DNA has the instructions for making a living thing. In people, this DNA is stored in 23 pairs of chromosomes.

Men and women both share the first 22 pairs. It is the 23rd pair that is different between men and women. Most males have an X and a Y chromosome, while most females have two X’s.

When a couple has a child, each parent passes one chromosome from each pair down to the child. What this means for the 23rd pair is that while mom always passes an X, dad can pass either an X or a Y. This is why the child’s sex is mostly determined by which chromosome is passed down by their father (X = female, Y = male).

Each child has a 50% chance to get dad’s X and a 50% chance to get dad’s Y. This is where the 50% chance for a boy and the 50% chance for a girl come from.

Sertoli Cell Only Syndrome (SCOS) happens when a specific part of a man’s Y chromosome functions differently than usual. So this means that only the kids that get dad’s Y would have it too. Which is why only boys will get it.

It is also why daughters will not pass SCOS onto their sons. They did not get a Y and do not have one to give. The sons of these women will get their Y chromosomes from their dad. This is also why daughters will not pass SCOS onto their sons: they don’t carry the condition in their DNA.

Given how SCOS is passed on, it might seem weird that anyone has this condition at all. Men can’t get it from their moms and until recently, they couldn’t get it from their dads either.

The answer is that it is not something they inherit from their parents. Instead it is something that happens to their DNA as their dad’s sperm is being made, or soon thereafter.

Genetics that Pop Up Out of Nowhere

We do not just have our parents’ DNA. Each of us has a few minor differences that are our very own. These are due to mutations.

Now, these mutations aren’t turning us into Wolverine or anything nearly so interesting. For the most part they are minor tweaks to a small part of the instructions for making or running us.

Most of the time these changes don’t do much of anything or have such subtle effects we don’t even notice them. But sometimes a small change can make a big difference.

Occasionally a small change will make what should have been a brown eye, blue. And sometimes it can cause problems like those seen in Sertoli Cell Only Syndrome (SCOS).

There are two big hotspots for mutations in our DNA, the Y chromosome and a tiny bit called the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Both tend to build up more differences than the rest of our DNA because they do not have a partner available to help fix any mistakes that are made. They are alone and so suffer.

There are a couple of major ways that these kinds of mutations happen. One is when something outside of us like chemicals, radiation, or viruses damages our DNA. This is just a partial list of the outside forces that can change our DNA.

Another major cause of mutations is when our cells do it to themselves. Each time a cell divides, it needs to copy its DNA. The copying machinery is good but it isn’t perfect. It occasionally makes a mistake during copying and that mistake can sometimes go on to become a mutation.

Luckily for us our cells have lots of ways to find and fix mutations. But one of these ways is not available to the Y chromosome.

This method of repair compares the two chromosomes in a pair and uses the undamaged copy to know how to fix the damaged one. Since the Y has no partner, this method is not available to it. This is a big reason why it builds up errors so much more quickly than our other chromosomes. And where many of the cases of SCOS come from.

Many people with SCOS have these kinds of mutations on their Y chromosome. As dad’s sperm was being made, the Y mutated in just the right spot to affect sperm production of the baby to be. In the near term, most of these men will probably never have kids of their own (although who knows what the future holds).

But a few men with SCOS do manage to eke out a few sperm. These can sometimes be collected and directly injected into an egg giving these men a shot at having a biological child of their own.

These lucky few will want to keep in mind that any sons they father will almost certainly have the same sorts of fertility issues. The only way around this is to just have daughters.

Author: Dr. Barry Starr

Barry served as The Tech Geneticist from 2002-2018. He founded Ask-a-Geneticist, answered thousands of questions submitted by people from all around the world, and oversaw and edited all articles published during his tenure. AAG is part of the Stanford at The Tech program, which brings Stanford scientists to The Tech to answer questions for this site, as well as to run science activities with visitors at The Tech Interactive in downtown San Jose.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation