How did people identify the remains of Richard III after 600 years?

February 8, 2013

- Related Topics:

- Ancestry,

- Ancient DNA,

- Forensics,

- Relatedness,

- History

A curious adult from California asks:

"I was reading about how they used DNA to identify the body of Richard III in England. How could they use 600 year old DNA to identify him?"

Reading DNA from old samples isn’t that big a deal anymore. We’re getting good enough at it to read Neanderthal DNA from tens of thousands of years ago. But this is something a little different.

Here researchers from the University of Leicester used old DNA to identify who a person was. With this you need to do more than read the DNA… you need to take that DNA and match it up to a living relative. And it turns out that the tricky part is finding the right relative, not reading the DNA.

DNA is passed down through generations

You probably know you share 50% of your DNA with each of your parents. And you probably know you share 25% of your DNA with your grandparents. The amount of DNA you share with relatives keeps getting cut in half like this as you move back through the generations.

If we say there are five generations each century, then anyone alive today is 30 generations removed from Richard III. Using the 50% number, that means even direct descendants of Richard III would only share about 0.0000001% of Richard III’s DNA. There is no way we’d see that! And luckily we don’t have to.

Y chromosomes and mtDNA stay consistent through time

There are two small bits of DNA that don’t get diluted each generation. They are the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) that is passed from mother to child and the Y chromosome that is passed from father to son. Each of these DNAs passes to the next generation virtually unchanged.

So all we have to do is follow those DNAs back in time from someone alive today back to Richard III. Easier said than done…

As you have already undoubtedly figured out, not every relative of Richard III will share these two specialized bits of DNA. To follow the Y chromosome, you need an unbroken male line. And to follow the mtDNA, you need an unbroken female line. It takes a lot of detective work and a bit of luck to find such a relative.

For example, if we are following the mtDNA (as these researchers did), then we need to start out with one of Richard’s sisters or his mother. He would not pass his mtDNA down to any of his direct descendants. Let’s say we start out with his sister.

Next we would need to find his sister’s daughters (Richard III’s nieces). If a sister had only sons, then that whole line is a dead end in terms of mtDNA. But if we find a niece, we next need to find a niece that had daughters. And so on for thirty or so generations.

If all these lines eventually end in only males, then we may need to go back up the family tree past Richard III. Maybe we need to focus on sisters of Richard III’s mother and follow those lines. Or sisters of Richard III’s mother’s mother (his maternal grandmother). And so on again.

Successful identification of King Richard III’s descendants

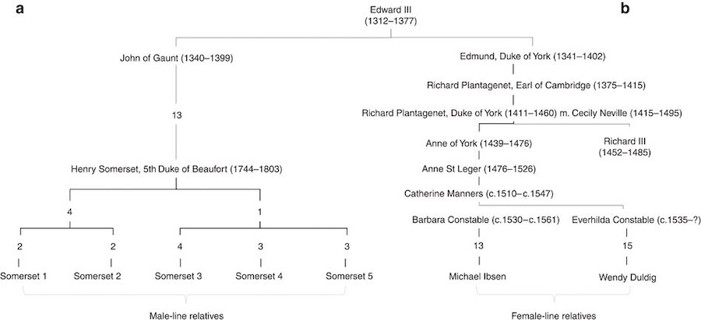

As you can see in the family tree below, the researchers did manage to find a man in Canada who is predicted to share mtDNA with Richard III. When his DNA was compared with that of the skeleton’s, the DNA matched. This was also true of a second woman who shared mtDNA.

They are also working on the Y chromosome to see if it matches any relatives alive today who would have been on a father to son line all the way back to Richard III’s son, John of Gaunt. The researchers have reported that they have found relatives and early work suggests that they may share Richard III’s Y chromosome.

So the mtDNA matches and so too might the Y chromosome. But this alone would not be enough to positively identify the body as lots of people in the past would share this DNA. No, they needed more evidence than this to say that the body was that of Richard III. And they have it.

Circumstantial evidence helps positively identify Richard III

The skeleton was found in the general area where Richard III was reported to have been buried. They also used carbon dating to show the skeleton was from a man who was alive sometime between 1450 and 1500. This is when Richard III died. Added to this is the fact that the skeleton had a series of wounds consistent with how Richard III was killed in battle.

All of this combined with the DNA evidence was enough to conclude that the skeleton was Richard III. A 600 year mystery has been cleared up with good archaeology and DNA science.

Read More:

- University of Leicester: Richard III DNA evidence

- Investigative Genetics: Finding Tsar Nicholas' family

- ScienceDaily: Going back to Mitochondrial Eve

- What is mitochondrial DNA?

Author: Dr. D. Barry Starr

Barry served as The Tech Geneticist from 2002-2018. He founded Ask-a-Geneticist, answered thousands of questions submitted by people from all around the world, and oversaw and edited all articles published during his tenure. AAG is part of the Stanford at The Tech program, which brings Stanford scientists to The Tech to answer questions for this site, as well as to run science activities with visitors at The Tech Interactive in downtown San Jose.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation