Can a father pass his mitochondrial DNA to his child?

May 31, 2012

- Related Topics:

- Mitochondria,

- Recombination,

- Rare events

A graduate student from Trinidad and Tobago asks:

"I was speaking to a friend of mine about the fact that mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is passed on only through the mother. But he told me that this theory was now being challenged. He said that new research says that the father also passed on his mtDNA to the child. This was news to me. Is this true?"

No it doesn’t appear to be. There was some debate a few years back, but the vast majority of evidence points to only the mother passing her mitochondria down to her kids.

The debate started when scientists found a single case where a father had passed his mitochondria down to his child. But since then, no other cases have been found. And frankly, if they were out there, we would have found them.

Scientists have looked at thousands upon thousands of people’s mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and have reported no other cases of fathers passing their mtDNA to their kids. None. This means that if it does happen, it is incredibly rare.

And this matters. A big part of our understanding of human history is based on mtDNA only being passed from mother to child.

Scientists have been able to determine that all humans alive today are related to a single woman who lived around 150,000 years ago. They have also been able to trace how people moved out of Africa and into the rest of the world using mtDNA.

None of this would be valid if fathers passed down their mitochondria too. In fact, even if it happened only some of the time, that still might be enough to mess with results. (Although it might have to happen a lot to really cause problems.)

Now I don’t want you to worry too much. Even if fathers passed on their mtDNA, we’d still have another bit of DNA available for us to track our genetic history — the Y chromosome. The Y is passed from father to son in a way that lets us look way back in time too (see below).

What I thought I’d do now is talk a bit about mitochondria and why fathers don’t pass them to their kids. And why this matters for our understanding of human history.

The Friend Within

Let’s start with some background. Mitochondria are organelles within the cells of animals and plants that help make the energy needed for growth. When you breathe in oxygen, mitochondria mix it with the food we eat to make energy.

This main function of the mitochondria doesn’t concern us here though. What we are interested in is its DNA. Scientists call it mitochondrial DNA or mtDNA for short.

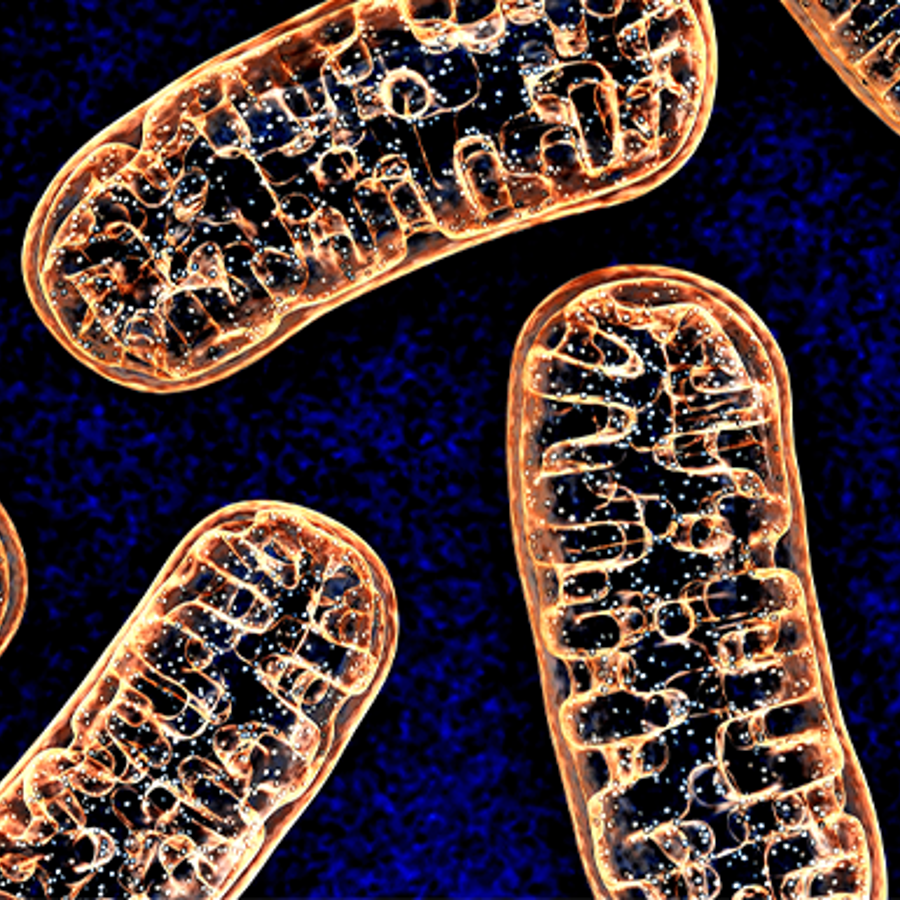

As you may know, most of your DNA -- the code that makes you you -- is stored in the cell nucleus. But there is a little bit of DNA in mitochondria too.

Scientists think that mitochondria have DNA because one or two billion years ago, they used to be free living bacteria. At some point, this free living cell took up residence in one of our ancestors. The rest is history.

This mtDNA only codes for a few genes, but it has proven to be an invaluable tool for scientists. As long as it just comes from mom.

Dilution and Destruction

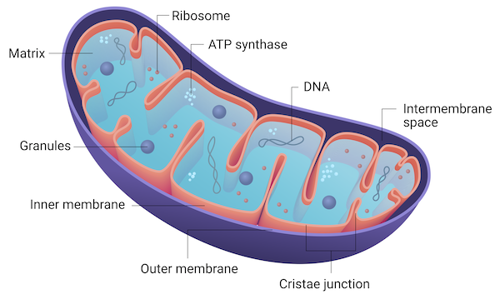

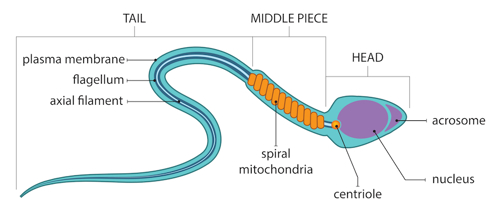

In fertilization, a sperm pretty much only contributes its DNA. Everything else that makes up a cell (called the cytoplasm) comes from the egg. And since mitochondria are in the cytoplasm, it makes sense that they mostly come from the egg.

But as you can see below, sperm do have some mitochondria. So it seems like a few should make it through. And a few probably do.

Scientists estimate that for every 1000 egg mitochondria, one sperm mitochondrion makes it into the egg. This is so few that they should mostly die out over time. But the egg takes no chances.

It has a system where it targets and destroys any stray sperm mitochondria. The end result is that none of the father’s mitochondria make it through.

Which is a good thing for evolutionary biologists! If paternal mitochondria made it through, all those studies I talked about would be ruined because of something called recombination.

Recombination - A Jumbled Swap Meet

As I talked about earlier, most of our DNA is found in the nucleus. It is stored there as chromosomes.

Most of us have 23 pairs of chromosomes for a total of 46. One from each pair comes from mom and the other from dad.

The way it works is that one of each pair is put into a sperm or an egg. This means that the sperm has 23 chromosomes and so does the egg. When the two come together in fertilization, you are back to 23 pairs.

So you get a chromosome 1 from mom and a chromosome 1 from dad. And a chromosome 2 from mom and a chromosome 2 from dad. And so on.

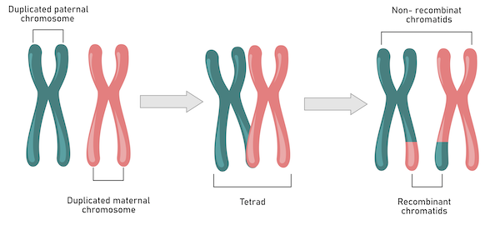

What is important for our story here is that the chromosome 1 you get from mom is not identical to either of hers. Instead it is a mixed combination of her two chromosome 1’s. The same is true of dad’s chromosome 1. And all of the other chromosomes except the mtDNA and the Y chromosome.

This DNA mixing is called recombination. And it makes tracing a person’s genetic history very difficult after just a few generations.

After multiple generations it gets really tricky to trace the chromosomal DNA. In fact, after only about five generations, the DNA gets so mixed up it becomes nearly impossible to trace.

This is why it is so important that mtDNA does not recombine. If dads passed on their mitochondria as well as moms, it would not be possible to trace inheritance from moms, to their moms, and their mom’s mom, etc.. The mtDNA would become incredibly mixed, so you couldn’t follow the line of one parent.

Luckily for scientists studying the human race’s genetic history, mom’s mtDNA has no partner to recombine with. Which means it is easy to trace back thousands of years.

Now as I said before, even if dad did pass on his mitochondria often enough to mess with scientists’ results, there is still another source scientists can trace. The Y chromosome in men.

Like mtDNA, this piece of DNA has no partner. So it is passed down from father to son with no recombination.

There you have it. There was a bit of hubbub a few years back about the possibility of mtDNA coming from dad too. But lots of work since then has shown this was an incredibly rare event.

Author: Justin Smith

When this answer was published in 2012, Justin was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying gene expression, evolution, and synthetic biology in Hunter Fraser’s laboratory. He wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation