Does the occurrence of mitochondrial dysfunction in a family cause autism?

December 6, 2012

- Related Topics:

- Autism,

- Mitochondria,

- Complex traits,

- Neurodiversity,

- Mutation

A curious adult from Georgia asks:

"If a grandmother has mitochondrial dysfunction, will a grandson have a greater chance of autism?"

Scientists are working hard to figure out why someone gets autism. They’ve found some things that seem to play a role and have ruled out some others. But they certainly haven’t found all, or even most, of the causes.

It doesn’t seem like having a grandmother with mitochondrial dysfunction raises your chances of having autism. This is even though mothers do pass on their mitochondria to their children. And even though problems with mitochondria probably do affect how severe your autism is and/or what symptoms you have.1

Around 1 in 20 people with autism have mitochondrial dysfunction. But only 1 in 4,000 people in general do.2 These numbers do seem to say that poorly working mitochondria might play a part in autism.

I said that mitochondria are passed on from your mother to you. So a grandson could get his mitochondria from his grandmother through her daughter. This is why it might seem weird that grandma’s problems with her mitochondria probably don’t affect her grandson or granddaughter’s autism risk.a

The tricky part is that not all problems with mitochondria are passed on from mother to child. Sometimes new mitochondrial problems pop up in a person. These new problems aren't always passed on.

A lot of things have to happen for a grandson to increase his risk of autism because of grandma’s mitochondria.2 Some of these are:

- The grandmother is the mother's mother.

- The mother passes on enough broken mitochondria to her son, the grandson.

- The grandson has other factors that predispose him to autism.

Most of the time these things don’t all happen. That’s why a grandmother’s poorly working mitochondria don’t look like they raise her grandson’s chance of autism.

So let’s talk about these criteria. What do mitochondria do and how do you get them? What happens when they don’t work and how does that affect autism?

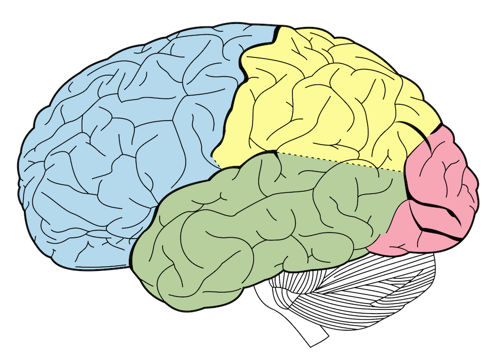

The Powerhouse of the Cell

Mitochondria are the part of a cell that makes the energy to do whatever the cell needs. So if the mitochondria aren’t working the body doesn’t have enough energy.

When your mitochondria don’t work normally this is called mitochondrial dysfunction. This can lead to poor growth, muscle weakness, and many other problems.2

One part of the body that needs a lot of energy is the brain. It makes sense that when mitochondria aren’t working properly, the brain doesn’t have the energy to work normally. That’s why people with mitochondrial dysfunction often have mental problems like learning disabilities or seizures.2

In autism the brain isn’t working in the usual way either. So it’s easy to see that having problems with mitochondria might make autism more severe.

For example, not having enough energy for the brain while a baby is growing in the womb might prevent the brain from developing normally. This may result in the child having certain developmental disorders, like autism.

But poorly working mitochondria on their own don’t seem to cause autism. After all, 19 out of 20 people with autism have normal mitochondria.2 So for mitochondrial dysfunction to affect autism, the person probably needs to already be predisposed to getting autism.1

I don’t have time to talk about what things do and don’t predispose someone towards having autism. That is a whole other set of answers. (Click here for more information on how someone might be predisposed towards autism.) Instead I’m going to focus on how mitochondria can be broken, and how people can develop problems with their mitochondria.

When the Power Goes Out

There’s lots of ways to mess up mitochondria. Some ways you can get from your parents and some appear new in you.

One way to mess up the way mitochondria work is to break the genes that make them run normally. Genes are pieces of DNA that have the instructions to build and run everything in our bodies.

A change in DNA (called a mutation) can break or change how a gene works. So mutations in any of the genes that tell mitochondria how to work might cause mitochondrial dysfunction.

New mutations are usually pretty rare, but there are a few exceptions. One of these is some special DNA found in the mitochondria.

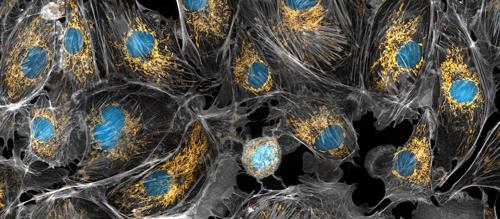

Most of our DNA is found on the chromosomes in a special place in the cell called the nucleus. But mitochondria also have a small amount of their own DNA called mtDNA. If mtDNA gets a mutation it can cause mitochondrial dysfunction, and this DNA happens to be especially prone to mutations.3

So grandma’s mitochondrial dysfunction could be something that she got from her parents or something that just happened in her. If the damage only happened in her, she might not pass it down to her children. That’s because it might only have happened in some cells in her body and not in her eggs.

Another reason she might not pass on mitochondrial dysfunction is because each cell has many mitochondria. Many people with mitochondrial problems have a mix of normal and broken mitochondria. If a mother with mitochondrial dysfunction happens to pass on those few working mitochondria her kids will be fine.3

Mutations in mtDNA aren’t the only way to knock mitochondria off of their game. Genes in the nucleus can also affect mitochondrial function. Either parent can pass on mutations in these genes.

Dysfunction can also happen with no impact on any DNA as a side effect of certain drugs or infections.3 Damage from these sources is very rarely passed on.

What all of this means is if you have mitochondrial dysfunction you probably don’t know how you got it. It could be from your parents, or from a new change in your DNA or something else entirely. And if you’re a mother you also don’t know which mitochondria you will give to your children.

You might have noticed that I keep talking just about mothers and grandmothers and ignoring dads. That’s because only moms and not dads pass on their mtDNA to the next generation.

Mitochondrial DNA

You probably know that you get your DNA from your parents. Half comes from your mom and half from your dad. While that’s true for the DNA in your nucleus, mtDNA doesn’t follow that rule. It only comes from your mother.4

The way this works is every cell, including sperm and eggs, has many individual mitochondria. When an egg is fertilized most of the sperm mitochondria remain in the tail of the sperm that falls off and doesn’t become part of the embryo. And the egg usually destroys any sperm mitochondria that do manage to make it in.4

That’s why grandma’s mtDNA matters. The only mitochondria and mtDNA you get comes from your mom. And a grandson will have his mother’s mother mtDNA but not his father’s mother’s.

But remember mitochondria also need DNA from the nucleus to work. Any changes to this DNA can also cause problems with mitochondria. And these mutations can be passed down from either parent.

Back to the Beginning

What all of this means is that a grandma with mitochondrial dysfunction probably does not pass on a higher chance for developing autism to her grandson. If she is the mother’s mother, and most of the mitochondria in her eggs are broken, and the grandson already has other risks for autism, then she might have passed down something that made her grandson’s autism a bit more severe. All those ands are why grandma’s mitochondria don’t really play an important role in autism risk!

Read More:

- National Human Genome Research Institute: More about mutations

- Scientific American: mtDNA mutations over time

- JAMA: Mitochondrial dysfunction and autism

- Annals of Human Genetics: Study suggests that mtDNA does not play a big role in autism risk

Author: Alisa Lehman

Barry served as The Tech Geneticist from 2002-2018. He founded Ask-a-Geneticist, answered thousands of questions submitted by people from all around the world, and oversaw and edited all articles published during his tenure. AAG is part of the Stanford at The Tech program, which brings Stanford scientists to The Tech to answer questions for this site, as well as to run science activities with visitors at The Tech Interactive in downtown San JoWhen this answer was published in 2012, Alisa was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biology, studying nitrogen fixation and symbiosis in Sharon Long’s laboratory. Alisa wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.se.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation