Can a paternity test be wrong if the tested man is related to the real dad?

September 29, 2010

- Related Topics:

- Paternity tests,

- Relatedness,

- Genetic testing,

- DNA sequencing

A curious adult from California asks:

“I have heard that paternity tests can be wrong if the real dad is related to the tested man. Is this true?”

Yes, that is true. If two men are closely related, then a standard paternity test might not be able to tell them apart. This means that in some situations, the wrong man could be identified as the biological father.

Imagine two brothers who might be the father of a child. For whatever reason, no one tells the paternity testing company that this is the case and so only one brother ends up getting tested.

The results show that the tested brother’s DNA matches the child’s, and so he is identified as the father. Except he isn’t the biological father. Both brothers happen to match the child in this DNA test.

What needed to happen here was for someone to tell the testing company upfront that either brother might be the biological father. Then the company could test both of them and do additional tests until one or the other brother was ruled out.

At first, this might all seem weird since, unless the brothers are identical twins, they don’t have the exact same DNA. You’d think this would mean that a DNA test would never confuse two people. And you’d be right if DNA tests looked at all of someone’s DNA. But most of them don’t.

Current DNA tests only look at a small fraction of anyone’s DNA. This is enough to tell unrelated people apart but it doesn’t always work for related people.

Related people share a lot of the same DNA. This makes them more likely to share the bits of DNA that get tested too. And this makes it more likely that they will be indistinguishable on some genetic tests.

This isn’t just a theoretical problem, either. A friend of mine at a paternity testing company tells me that these issues really do come up. And they will keep coming up until DNA testing prices come down.

At some point, DNA testing may become cheap enough for companies to look at most or all of someone's DNA. Until that time, we’ll probably have to keep using the same paternity tests. So to get the right answer, you need to pick a good testing company and give them all of the facts.

Today’s Paternity Tests

A paternity test compares a small part of a child’s DNA to a small part of a potential father’s DNA. A common test looks at 15 or so of these spots.

The spots they are comparing have lots of different names. They’re called microsatellites, simple sequence repeats (SSRs), short tandem repeats (STRs), or variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs).

These are places in the DNA where a certain bit of DNA is repeated. For example, some people may have 10 copies of ATGC at a certain site while others might have 9 or 11 or whatever.

So that’s what it means when you get a “D3S1358, 17/18” on your test. You have 17 repeats on one chromosome and 18 on the other at D3S1358, a certain spot on a chromosome.

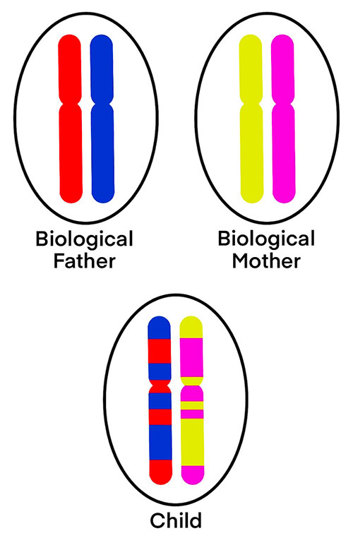

You have a 17 and an 18 because you have two copies of each of your chromosomes (except for the X and the Y chromosomes in men). One chromosome of each of your pairs came from your biological mother and the other from your biological father.

Let’s look at a single marker to see how this kind of test works. Imagine that the biological mother, child, and potential father have the following markers at D3S1358:

- Mother: 13, 14

- Potential Father: 17, 18

- Child: 13, 18

In this case, the biological mother gave the child a 13 and so the father had to give the child an 18. This potential man could be the father in this case since he has an 18 to give.

Of course a lot of men have an 18 at that position too. This is why testing companies look at more than one spot. The more DNA they look at, the more confident they can be that a certain man is the biological father. Or that he isn’t.

Brothers Share a lot of DNA

The number of markers that testing companies look at works great for unrelated men. It is very unlikely that two random men will match up at all 12, 15, or 20 markers.

But brothers aren’t two random men. They have the same biological mother and father and so share around 50% of their DNA.

What this means is that they are more likely to match up at some or even all of the tested sites. And therefore they are more likely to each pass the same DNA markers to their kids.

This is where the trouble can start. If two brothers happen to share markers at all of the sites tested, then the wrong man can be identified as the biological father.

But again, unless they are identical twins, the brothers will not match up at every DNA position. If a company looks at enough DNA, they will be able to tell who the biological father is. And a company will do this if you tell them that either brother might be the biological father.

An Example

I’ll end with an example to make this all more concrete. To simplify things, I’ll start off with just 10 markers. Here is a test result for biological mother, child, potential father 1 (brother 1), and potential father 2 (brother 2):

|

Marker |

Biological Mother |

Child |

Potential Father 1 |

Potential Father 2 |

|

A |

13, 15 |

13, 13 |

13, 13 |

13, 13 |

|

B |

9, 12 |

9, 12 |

8, 12 |

12, 17 |

|

C |

11, 13 |

11, 14 |

14, 14 |

14, 14 |

|

D |

29, 31 |

27, 31 |

25, 27 |

27, 27 |

|

E |

16, 21 |

16, 22 |

21, 22 |

22, 23 |

|

F |

14, 17 |

14, 19 |

16, 19 |

19, 19 |

|

G |

16, 28 |

16, 19 |

19, 28 |

19, 25 |

|

H |

12, 12 |

12, 15 |

12, 15 |

15, 15 |

|

I |

7, 9 |

7, 9 |

6, 7 |

6, 7 |

|

J |

8, 8 |

8, 8 |

8, 8 |

8, 8 |

In this example, the markers from the biological mother are in pink and the markers from the potential fathers are in blue. If just potential father 1 were tested, then he would be identified as the biological father even though he might not be.

Luckily for everyone involved, both potential fathers are tested. Since the first batch of results was inconclusive, more extensive testing is done. Here are the results:

|

Marker |

Biological Mother |

Child |

Potential Father 1 |

Potential Father 2 |

|

A |

13, 15 |

13, 13 |

13, 13 |

13, 13 |

|

B |

9, 12 |

9, 12 |

8, 12 |

12, 17 |

|

C |

11, 13 |

11, 14 |

14, 14 |

14, 14 |

|

D |

29, 31 |

27, 31 |

25, 27 |

27, 27 |

|

E |

16, 21 |

16, 22 |

21, 22 |

22, 23 |

|

F |

14, 17 |

14, 19 |

16, 19 |

19, 19 |

|

G |

16, 28 |

16, 19 |

19, 28 |

19, 25 |

|

H |

12, 12 |

12, 15 |

12, 15 |

15, 15 |

|

I |

7, 9 |

7, 9 |

6, 7 |

6, 7 |

|

J |

8, 8 |

8, 8 |

8, 8 |

8, 8 |

|

K |

13, 17 |

13, 19 |

15, 19 |

19, 19 |

|

L |

6, 8 |

3, 8 |

3, 7 |

3, 3 |

|

M |

15, 18 |

2, 15 |

3, 5 |

2, 2 |

|

N |

17, 19 |

17, 18 |

9, 18 |

7, 18 |

|

O |

18, 22 |

18, 22 |

18, 18 |

18, 18 |

When we add five more markers, potential father 1 now has a mismatch (in red). Now if we don’t test potential father 2 as well, this still isn’t enough to exclude potential father 1. For reasons we talk about here, a single mismatch sometimes naturally happens, so this won't usually rule out a candidate being the biological father. This means we still need some additional testing to find the biological father:

|

Marker |

Biological Mother |

Child |

Potential Father 1 |

Potential Father 2 |

|

A |

13, 15 |

13, 13 |

13, 13 |

13, 13 |

|

B |

9, 12 |

9, 12 |

8, 12 |

12, 17 |

|

C |

11, 13 |

11, 14 |

14, 14 |

14, 14 |

|

D |

29, 31 |

27, 31 |

25, 27 |

27, 27 |

|

E |

16, 21 |

16, 22 |

21, 22 |

22, 23 |

|

F |

14, 17 |

14, 19 |

16, 19 |

19, 19 |

|

G |

16, 28 |

16, 19 |

19, 28 |

19, 25 |

|

H |

12, 12 |

12, 15 |

12, 15 |

15, 15 |

|

I |

7, 9 |

7, 9 |

6, 7 |

6, 7 |

|

J |

8, 8 |

8, 8 |

8, 8 |

8, 8 |

|

K |

13, 17 |

13, 19 |

15, 19 |

19, 19 |

|

L |

6, 8 |

3, 8 |

3, 7 |

3, 3 |

|

M |

15, 18 |

2, 15 |

3, 5 |

2, 2 |

|

N |

17, 19 |

17, 18 |

9, 18 |

7, 18 |

|

O |

18, 22 |

18, 22 |

18, 18 |

18, 18 |

|

P |

3, 7 |

3, 12 |

5, 8 |

8, 12 |

|

Q |

26, 28 |

9, 28 |

9, 9 |

9, 9 |

|

R |

5, 6 |

4, 5 |

6, 12 |

4, 12 |

|

S |

9, 10 |

9, 12 |

12, 18 |

12, 17 |

|

T |

13, 22 |

13, 19 |

17, 23 |

14, 19 |

Now we’re getting some results that can tell these two men apart. Potential father 1 has 4 mismatches while potential father 2 has none. Almost certainly potential father 2 is the biological father.

If the first test had been done on just potential father 1, he would be identified as the biological father. And might be raising his brother’s child as his own!

Luckily everyone was honest with a very good testing company. Together they were able to figure everything out.

As a final note, 20 markers may not even be enough. I know of a case where two potential fathers were identical at 21 of 23 markers and who shared a marker at the other two.

In this case, if the testing company looked at the identical 21, they wouldn’t be able to distinguish between these two men as fathers. And even if they looked at 23, there would be a 1 in 4 chance that you still couldn't tell who the biological father was even with 23 markers!

Author: Dr. Barry Starr

Barry served as The Tech Geneticist from 2002-2018. He founded Ask-a-Geneticist, answered thousands of questions submitted by people from all around the world, and oversaw and edited all articles published during his tenure. AAG is part of the Stanford at The Tech program, which brings Stanford scientists to The Tech to answer questions for this site, as well as to run science activities with visitors at The Tech Interactive in downtown San Jose.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation