If I have type 1 diabetes, what is the chance that my children will too?

July 30, 2009

- Related Topics:

- Diabetes,

- Complex traits,

- Autoimmune disease,

- Epigenetics,

- Environmental influence

A curious adult from California asks:

“If I am a type 1 diabetic (since 25 years) – what is the probability that due to genetic transformation my child/children could be diabetics too? Is it true that type 1 diabetics are genetically inherited from ancestors or is it a combination of factors?”

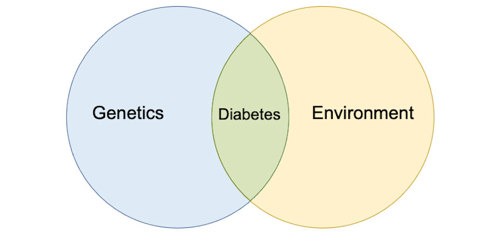

Type 1 diabetes happens because of a combination of factors. It is partly genetic. But the environment plays a role too.

We know that if one parent has Type 1 diabetes, then each child is 10 times more likely to get Type 1 diabetes too.1 This might sound scary, but the actual risk of getting Type 1 diabetes isn’t that high.

The average person has around a 1 in 200 chance of developing Type 1 diabetes. So if you have a parent with it, your chances become around 1 in 20. Or in other words, you have a 5% chance of also becoming diabetic.

Now this doesn’t give you a lot of information about your specific situation. That 5% is made up of a large group of people. Some have a much higher risk and some have a much lower risk.

This information does tell us that genes are almost certainly involved in Type 1 diabetes. But other information tells us they aren’t the whole story.

One way we know this is because of identical twin studies. Identical twins have the same set of genes. So if a disease were just due to genes, when one twin has it, then the other would always have it too.

But this is not the case with Type I diabetes. If one twin has it, the other twin gets it less than 50% of the time, even if they are identical.2 There must be something else going on here.

Most likely something from the environment needs to trigger the development of Type I diabetes. Genes make that trigger more or less likely to cause the disease.

Scientists are hard at work trying to figure out what these environmental triggers are and what genes are involved. But before we discuss some of these, let’s first take a step back and see what happens in Type I diabetes. Then we can see how some of the over 20 genes thought to be involved might influence the development of the disease.*

An Immune System Gone Wrong Causes Type I Diabetes

To be used by the body for energy, food must be broken down into sugars. These sugars then travel through the blood to the cells that need them.

People with Type I diabetes have trouble regulating the amount of sugar in their blood. They tend to have very low levels right before eating and high levels right after.

This is dangerous because a high level of sugar in the blood can damage the eyes, nerves, and kidneys. It can also increase the risk of heart attack, stroke, and high blood pressure.

Normally the amount of sugar in the blood is controlled by insulin. When there is too much sugar, insulin helps to move it into the cells. This helps keep blood sugar constant.

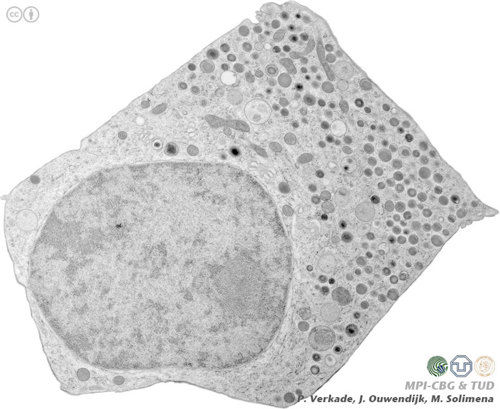

Type I diabetics can’t make their own insulin. Their immune systems have gone haywire and attacked the cells that make insulin – the beta cells of the pancreas. This attack destroys the beta cells so that no insulin is made.

As I said before, Type 1 diabetes risk involves at least twenty different genes. So there are lots of different reasons people can have a higher risk of getting this disease.

One reason it happens more often in certain people is because of the particular versions of immune genes that they have. These genes can make a person more susceptible to thinking one of its own cells is a foreign invader that needs to be destroyed.

Genes, Triggers, and the Immune System

Remember, genes have the instructions for making and running our bodies. This includes our immune system.

Basically, each gene has the instructions for a single protein. And each of these proteins does a specific job in the body.

There are genes for our immune system called HLA (or Human Leukocyte Antigen) genes. The proteins made by these genes are used as an alarm for something that has invaded the body. They are like the touchpad in a home security system.

To get into one of these houses, you need to type in the right code into the touchpad. Otherwise, a siren goes off and the police come.

The same thing happens in the cells. Only instead of a touchpad, the body uses the HLA proteins on the outside of cells. When an invader shows the HLA proteins an unknown protein (like an unknown code), the immune system is activated. And the invader is destroyed.

In fact, any cell that shares the same unknown protein is destroyed too. This is how the body can fight off millions of viruses and bacteria. But this is also how the trouble starts in an autoimmune disease like Type 1 diabetes.

Some people have a version of the touchpad that makes it easier to mix up the code of an invader with a beta cell in the pancreas. When the HLA protein misreads a beta cell code as that of an invader, the beta cells are attacked. The end result is no beta cells and Type I diabetes.

Not everyone with this version of the HLA gene ends up with Type I diabetes though. So something else has to happen.

That something might be an invading virus that has a protein that kind of looks like one on a beta cell. It is known that certain viral infections cause an increased risk.

Or it could be something less obvious. Early diet may play a role and breastfeeding might lower the risk. Environmental factors, such as cold weather, can also increase the risk.

Scientists are working really hard to try to figure out what the real triggers might be. And how to make them less likely to cause Type 1 diabetes.

One hope is that scientists will find that certain triggers are particularly bad for people with certain HLA genes. If someone knows that, then the person can avoid that trigger at all costs and not worry so much about other ones.

*According to a study published in 2013, the number of genes involved in Type 1 diabetes is actually 59.

Read More:

- National Center for Biotechnology Information: Genetic Factors in Type I Diabetes

- American Diabetes Association: The Genetics of Diabetes

- ABCNews: Diabetes Risk for Kids of Diabetics?

Author: Gwen Liu

When this answer was published in 2009, Gwen was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Microbiology & Immunology, studying the structure and function of microRNA genes in Chang-Zhen Chen’s laboratory. Gwen wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation