Is the tendency for anger genetic?

January 6, 2005

- Related Topics:

- Complex traits,

- Personality traits,

- Environmental influence

A high school student from California asks:

Editor’s Note (5/21/2021): In the 16 years since this article was originally published, scientists have made some progress in understanding how our genes affect our personality. For a more recent paper on this topic, see this review on the Human Affectome Project.

Wow, this one was a toughie! What we are really talking about here is getting angry easily. Some work in behavioral genetics suggests that this trait can be partially inherited. But it certainly isn’t purely genetic! Whether someone gets angry often isn’t written in their DNA.

As anyone who has kids can tell you, there are some parts of personality that seem to be hard wired. However, personality is a complex trait that can be hard to define and predict. And it’s definitely informed by more than just your genes alone.

Scientists who have studied this have found that one of the strongest inherited genetic traits is something they’ve called “temperament”.

Temperament is made up of three parts – “emotionality”, “activity level” and “sociability”. What we're interested in here is emotionality. Emotionality is how easily someone gets scared or mad in upsetting situations.

From lots of different studies of twins, it looks like about half of our emotionality is inherited. The other half comes from where we live, how we're raised, etc.

Now, it’s important to note that “emotionality” is not the same thing as “gets angry easily”. Since emotionality was defined in these personality studies as including a few different types of emotions, it’s not a perfect comparison. But this is the closest data I could find for your question. Maybe someday there will be more research about anger specifically! But how could something like how quickly we get angry be inherited at all?

To be inherited, genes have to be involved somehow. It turns out that genes can affect your brain chemistry, which can in turn affect how someone responds to upsetting situations.

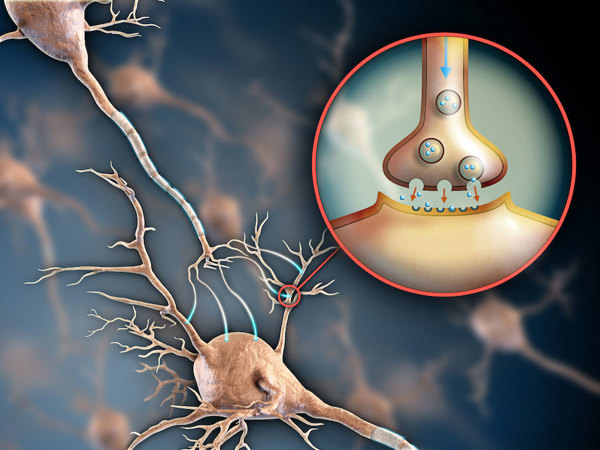

Anger happens when something around us causes a bunch of chemicals to be released in the brain. These chemicals (called neurotransmitters) then eventually tell the body to make our hearts beat faster, increase our blood pressure, etc.

How do these chemicals work? They attach themselves to special proteins called receptors and turn them on. Once enough receptors are turned on, other proteins are turned on as well. Eventually you get something to happen like a pupil dilating or palms sweating.

One example of genes that could be involved in our anger response are the ones related to the chemicals and receptors. (There are lots of other ways too but we'll use this as an example.) Remember, these chemicals and the receptors are made from instructions found in genes.

Right now, we don’t understand fully how genes are involved in the anger response, but we can make some educated guesses. Here, we’re going to talk about a few ways that genes might be affecting how people experience anger. But again, we don’t know for sure.

What if some people had a version of a gene that resulted in a stronger chemical being made? Or more of the chemical being made in a certain situation? Or a receptor that needs less chemical to work? They'd all get angry more easily.

Maybe a concrete example will make this easier to understand. Let’s say Bob gets mad when he tries to program his DVD player but Sam doesn't. Let’s say it takes 100 of a "normal" chemical to generate an anger response.

Sam might make only 90 but Bob makes 110 in this situation. Or Bob makes 90 but they're stronger or his receptor is more sensitive so it is enough to get him mad.

Of course, it most likely isn’t that simple. There are probably hundreds of genes involved in such an important response, all affecting each other. And we need to remember that it isn't all genes – half of our emotionality comes from our environment.

Genetically, the next research step is to figure out the genes involved. While this won't be easy, research on this topic is helped by the fact that animals get angry too and have similar responses. Also, there are some mental diseases that result in getting angry quickly. Understanding these diseases at a genetic level should give us some idea of how “normal” anger happens.

Finally, with the sequencing of all of the DNA in humans, scientists can begin to look at the small changes that make us all unique. If they compare people who get angry easily and less excitable people, they may be able to pick out the changes involved.

At least right now, not much is known about anger specifically. Emotions and personality are complicated, and we have a lot more research to do before we fully understand these topics!

Read More:

- How a twin study works

- Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: Behavioral Genetics and Child Temperament

- American Psychological Association: When anger’s a plus

Author: Dr. D. Barry Starr

Barry served as The Tech Geneticist from 2002-2018. He founded Ask-a-Geneticist, answered thousands of questions submitted by people from all around the world, and oversaw and edited all articles published during his tenure. AAG is part of the Stanford at The Tech program, which brings Stanford scientists to The Tech to answer questions for this site, as well as to run science activities with visitors at The Tech Interactive in downtown San Jose.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation